I'm late to the game on this, but I just started watching the Baroness Von Sketch show this season, and I'm really enjoying it.

One little thing I appreciate is when a sketch involves a couple but the gender of the couple is irrelevant to the sketch, they most often make it a same-sex couple played by two of the (all-female) leads.

Here's an example:

That sketch is entirely gender-irrelevant. It would have worked out the same way regardless of the genders of the characters. So they simply cast two of the leads as characters who are the same demographic as the actors - two women played by two women.

If you think back to older sketch comedies like Monty Python or Kids in the Hall, they wouldn't do that. If the genders of the couple were irrelevant to the sketch, they'd make it an opposite-sex couple. They'd only use same-sex couples if there was a specific reason why a same-sex couple was needed.

But another thing that Monty Python and Kids in the Hall often did was have female characters portrayed by the all-male leads rather than using a female supporting actress to play a female character. They did use female supporting actresses as well (just as Baroness Von Sketch uses male supporting actors), but the default seemed to be a male lead dressed as a woman.

If you think about it, it's kind of bizarre that in a sketch comedy environment that couldn't perceive a same-sex couple neutrally, a sketch comedy couple consisting of one male actor dressed as a man and one male actor dressed as a woman was seen as neutral and unmarked (in the linguistic sense).

Someday in the future, probably sooner than we expect, people are going to watch those sketches and think all the Monty Python pepperpots are meant to be trans or genderqueer, and they'll need a historical explainer to understand what the Pythons are doing. And they're going to think this post, noticing that gender-irrelevant couples are portrayed as same-sex couples by the all-female cast, is going to come across as having homophobic undertones, like how someone's grandmother who gratuitously mentions the race of everyone she brings up in conversation comes across as having racist undertones.

Showing posts with label musings. Show all posts

Showing posts with label musings. Show all posts

Monday, December 17, 2018

Friday, November 16, 2018

Outdoors ≠ simple

From a recent Carolyn Hax chat:

I think this letter-writer is falling into a common cultural trap: the notion that outdoors = simple.

People tend to think this because conventional wisdom is that life was simpler in the past, and in the distant past people spent more time outdoors simply because their homes were less adequate.

But now we live in a world where our homes and other buildings meet our basic needs significantly better than the outdoors does, which makes spending time outdoors more complex.

For example, in our homes we have clean, private places where we can urinate and defecate, equipped to clean our genitals and our hands to a socially-acceptable and hygienically-necessary level afterwards. So when we go outdoors, finding a place to urinate or defecate and a way to clean up afterwards adds complexity. We either have to figure out where there's a public washroom, or take equipment with us and find a place with suitable privacy. (And, for those of us who aren't used to going to the bathroom outdoors, there's the question of logistics and choreography - personally, I haven't a clue what angle anything is going to come out at, and I'm not sure how long I can stay in the necessary squatting position.)

In our homes, we have facilities to store food at a safe temperature, and equipment to serve and consume food and drink in accordance with social norms. So when we go outdoors, we have to think about food safety. (How can we keep the food cold? Or what food doesn't need to be refrigerated?) We also need to think about how we're going to store the food, so we can carry it with us, so it doesn't spill and so ants and raccoons and cartoon bears don't eat it.

In our homes, we are sheltered from the elements. So when we go outdoors, we have to think about the elements. Do we need clothing and/or equipment to protect us from the heat/cold/sun/rain/snow?

Because of all that, the simplest way to have a wedding is at a place already designed to host weddings (or perhaps other events), which is most likely to be indoors or have an indoor component. Being in an existing, operating building, a wedding venue would have bathrooms and shelter from the weather and provisions for parking. Because its whole job is hosting weddings/events, it would already be prepared with chairs, wouldn't have to inform the neighbours because they'd already know it's an event venue, and wouldn't have to fix the lawn because they'd already have landscaping etc. that could stand up to a wedding being held there. You could practically go in and say "One wedding please, whatever's cheapest and simplest."

If outdoors is important to you for whatever reason, go ahead and plan something outdoors. If the real issue is that you don't want to pay for a venue, go ahead and try to impose on your loved ones for a space. But if what you want really is simplicity, that's going to be far more difficult to achieve outdoors.

Dear Carolyn, My fiancé and I want a small, backyard wedding with about 75 guests. My grandmother has a huge yard that would be perfect for our wedding next spring. I asked her if we could get married there and she said yes, so I was very excited to start planning. Then last weekend I had lunch with my sister. She told me that our grandmother is too old and isn’t well enough physically to get her house ready to host an event like this so our mother will be doing most of the work. I told her it was an outdoor wedding, all we have to do is get some chairs and everything will work out. My sister started telling me I have to plan for parking, bathrooms, permits, chairs, a tent for bad weather, alerting the neighbors, hiring a lawn company to fix up our grandmothers lawn and I’m sure I am forgetting stuff. I just wanted a simple backyard wedding and my grandma agreed to it, now it feels really complicated. I am upset with my mother and sister for inserting themselves into something that ought to be between me and my grandma. How can I get them to back off?

I think this letter-writer is falling into a common cultural trap: the notion that outdoors = simple.

People tend to think this because conventional wisdom is that life was simpler in the past, and in the distant past people spent more time outdoors simply because their homes were less adequate.

But now we live in a world where our homes and other buildings meet our basic needs significantly better than the outdoors does, which makes spending time outdoors more complex.

For example, in our homes we have clean, private places where we can urinate and defecate, equipped to clean our genitals and our hands to a socially-acceptable and hygienically-necessary level afterwards. So when we go outdoors, finding a place to urinate or defecate and a way to clean up afterwards adds complexity. We either have to figure out where there's a public washroom, or take equipment with us and find a place with suitable privacy. (And, for those of us who aren't used to going to the bathroom outdoors, there's the question of logistics and choreography - personally, I haven't a clue what angle anything is going to come out at, and I'm not sure how long I can stay in the necessary squatting position.)

In our homes, we have facilities to store food at a safe temperature, and equipment to serve and consume food and drink in accordance with social norms. So when we go outdoors, we have to think about food safety. (How can we keep the food cold? Or what food doesn't need to be refrigerated?) We also need to think about how we're going to store the food, so we can carry it with us, so it doesn't spill and so ants and raccoons and cartoon bears don't eat it.

In our homes, we are sheltered from the elements. So when we go outdoors, we have to think about the elements. Do we need clothing and/or equipment to protect us from the heat/cold/sun/rain/snow?

Because of all that, the simplest way to have a wedding is at a place already designed to host weddings (or perhaps other events), which is most likely to be indoors or have an indoor component. Being in an existing, operating building, a wedding venue would have bathrooms and shelter from the weather and provisions for parking. Because its whole job is hosting weddings/events, it would already be prepared with chairs, wouldn't have to inform the neighbours because they'd already know it's an event venue, and wouldn't have to fix the lawn because they'd already have landscaping etc. that could stand up to a wedding being held there. You could practically go in and say "One wedding please, whatever's cheapest and simplest."

If outdoors is important to you for whatever reason, go ahead and plan something outdoors. If the real issue is that you don't want to pay for a venue, go ahead and try to impose on your loved ones for a space. But if what you want really is simplicity, that's going to be far more difficult to achieve outdoors.

Labels:

advice columns,

musings

Sunday, November 11, 2018

Polite conversation and consent

Reading this Ask A Manager discussion about conversation topics that are totally off-limits in the workplace, I developed a theory:

The rules of polite conversation are essentially there to keep conversation consensual.

For example, religion is off-limits because not everyone consents to being converted or to being told their beliefs are Bad and Wrong or to being interrogated about and asked to defend their beliefs.

Politics are off-limit because not everyone consents to being converted or being debated or being told their core values are Bad and Wrong or being told Those People are Bad and Wrong.

Family planning is off-limits because not everyone consents to disclosing or being pressured to disclose the personal details of their medical history and their sex life and finances and interpersonal dynamics in their home.

And consent is all the more important in places like the workplace (and, I'd like people to start believing, the family) where there are power dynamics, and you can't just walk away and never speak to the people again.

Now, sometimes people do discuss these topics consensually. But, as with everything in life, it is important to make sure you truly do have consent first, and that the person is giving consent of their own free will rather than feeling pressured into it.

Some people will argue "There's no need for all these rules! If they don't want to talk about something, they should just say so!"

But enough people who don't feel they can say no have gathered enough empirical evidence that they'll suffer negative consequences ("Not a team player" "C'mon, lighten up!") that they don't feel safe saying no.

So if you want to live in a world where no topics are off-limits because people can just say no, start by influencing your corner of the world in a direction where people aren't shamed or spoken of negatively for not wanting to talk about something.

Just as more advanced sex acts, (e.g. BDSM), require a more robust consent environment, (e.g. safe words), so do more advanced conversation topics.

The rules of polite conversation are essentially there to keep conversation consensual.

For example, religion is off-limits because not everyone consents to being converted or to being told their beliefs are Bad and Wrong or to being interrogated about and asked to defend their beliefs.

Politics are off-limit because not everyone consents to being converted or being debated or being told their core values are Bad and Wrong or being told Those People are Bad and Wrong.

Family planning is off-limits because not everyone consents to disclosing or being pressured to disclose the personal details of their medical history and their sex life and finances and interpersonal dynamics in their home.

And consent is all the more important in places like the workplace (and, I'd like people to start believing, the family) where there are power dynamics, and you can't just walk away and never speak to the people again.

Now, sometimes people do discuss these topics consensually. But, as with everything in life, it is important to make sure you truly do have consent first, and that the person is giving consent of their own free will rather than feeling pressured into it.

Some people will argue "There's no need for all these rules! If they don't want to talk about something, they should just say so!"

But enough people who don't feel they can say no have gathered enough empirical evidence that they'll suffer negative consequences ("Not a team player" "C'mon, lighten up!") that they don't feel safe saying no.

So if you want to live in a world where no topics are off-limits because people can just say no, start by influencing your corner of the world in a direction where people aren't shamed or spoken of negatively for not wanting to talk about something.

Just as more advanced sex acts, (e.g. BDSM), require a more robust consent environment, (e.g. safe words), so do more advanced conversation topics.

Labels:

advice columns,

musings

Things I Don't Understand: objecting to assisted dying when you don't mind if people die

This post was inspired by, but is not directly related to, this op-ed outlining how the new provincial government's policies could kill people.

Policy can kill people. Politicians who enact such policies and other proponents of these policies either don't care if people die, or see people's deaths as acceptable collateral damage.

What's weird is the intersection between not caring if one's policies kill people, but being opposed to medically-assisted death. If you don't care if people die, why would you object to people dying?

Some people hold the idea that people should contribute to society rather than being a burden to society. Others refute argue against this idea, saying that your value comes from who you are as a person rather than what you can contribute. (I actually don't hold either of these ideas - I don't feel it's my - or anyone's - jurisdiction to go around insisting others contribute to my satisfaction or accusing others of being a burden, but I also don't feel that every human being has intrinsic value for the simple reason that I can't perceive any intrinsic value in my own essential humanity.)

So I also find it weird when people who hold the "contribute to society or you're a burden" idea are opposed to assisted death. In a paradigm where it is possible for a person to be a burden, why would you be opposed to someone saying "I'm too much of a burden, so I'm going to get out of the way now.

One reason I have heard for objecting to medically-assisted death while not objecting to death itself is that if you can do it yourself, you don't need medical assistance.

But the benefit of medically-assisted death rather than suicide is it doesn't leave a mess for other people to clean up. Currently, we don't have any non-medical method of suicide that doesn't leave a carcass in a place where it's inconvenient to others for there to be a carcass.

In contrast, in medical settings where people die, they're fully trained and prepared to move a dead body and hygienically clean up afterwards. (In my grandmother's long-term care home, they have whole procedures in place for this eventuality!) Until we have Suicide Place, medical contexts are our only option for people to die without being an undue burden upon others.

So it's really strange to me that people who don't mind that their policies might kill people are opposed to people choosing to die.

Policy can kill people. Politicians who enact such policies and other proponents of these policies either don't care if people die, or see people's deaths as acceptable collateral damage.

What's weird is the intersection between not caring if one's policies kill people, but being opposed to medically-assisted death. If you don't care if people die, why would you object to people dying?

Some people hold the idea that people should contribute to society rather than being a burden to society. Others refute argue against this idea, saying that your value comes from who you are as a person rather than what you can contribute. (I actually don't hold either of these ideas - I don't feel it's my - or anyone's - jurisdiction to go around insisting others contribute to my satisfaction or accusing others of being a burden, but I also don't feel that every human being has intrinsic value for the simple reason that I can't perceive any intrinsic value in my own essential humanity.)

So I also find it weird when people who hold the "contribute to society or you're a burden" idea are opposed to assisted death. In a paradigm where it is possible for a person to be a burden, why would you be opposed to someone saying "I'm too much of a burden, so I'm going to get out of the way now.

One reason I have heard for objecting to medically-assisted death while not objecting to death itself is that if you can do it yourself, you don't need medical assistance.

But the benefit of medically-assisted death rather than suicide is it doesn't leave a mess for other people to clean up. Currently, we don't have any non-medical method of suicide that doesn't leave a carcass in a place where it's inconvenient to others for there to be a carcass.

In contrast, in medical settings where people die, they're fully trained and prepared to move a dead body and hygienically clean up afterwards. (In my grandmother's long-term care home, they have whole procedures in place for this eventuality!) Until we have Suicide Place, medical contexts are our only option for people to die without being an undue burden upon others.

So it's really strange to me that people who don't mind that their policies might kill people are opposed to people choosing to die.

Sunday, September 30, 2018

Dear Miss Manners: what if you're bereaved and have poor acting skills?

From a recent Miss Manners:

But, as the kind of socially-inept person who reads an etiquette advice column to better myself, I have another question: what if you are bereaved but, for whatever reason, don't have the acting skills to represent the deceased to the other mourners?

Is Miss Manners saying you shouldn't attend the funeral in that case? Is there an etiquette-sanctioned way to attend the funeral but avoid people?

The family member whose behaviour so appalled the letter-writer and Miss Manners is the deceased's daughter's aunt, which, by my math, makes her either the deceased's sister or sister-in-law.

If we were to make a hierarchy about such things, the general consensus would be that the deceased's sister attending the funeral is more important than the members of the deceased's church getting their emotional needs attended to. If we were to analyze the situation under Ring Theory, the sister would be the one who gets to do the dumping, and the letter-writer would be the one who has to do the comforting.

So would Miss Manners advise a person on an inner ring to skip a funeral if they can't attend to the emotional needs of a person on an outer ring? Or does etiquette have something else in mind for people who, in their grief, just can't hold it together enough to fulfill the requirements of etiqutte?

Dear Miss Manners: At the funeral of a very dear person who was a founding member of the church I attend, I approached the deceased's sister outside the church before the service. I attempted to hug her and express my condolences. The sister all but recoiled, stating that she was not accepting any displays of condolence because it was "too upsetting" to her. Another family member, who was standing nearby at the time, just looked at me with a kind of "what-can-you-do?" expression on her face.

I was stunned and somewhat embarrassed because other people standing near enough heard her say this. I have not seen this person since the funeral about one month ago, and I am still a little rubbed about her behavior.

Should I be? She even made a remark to the effect that she knew her niece — the deceased's daughter — would probably hear about it and be upset with her, but that she didn't care.Miss Manners replies:

Thus both admitting and defending being rude to you.

Although we try to make allowances for the emotional state of those in fresh mourning, that does not include hurting other mourners by repulsing condolences. On the contrary, the immediately bereaved should be representing the deceased to those who also feel their loss.

Miss Manners did address the letter-writer's question, and did address the letter-writer's hidden question about whether it was appropriate for the family member in question to behave that way.So yes, Miss Manners agrees that you should be a little rubbed about this behavior. And that for the sake of your late friend, you will now let it go.

But, as the kind of socially-inept person who reads an etiquette advice column to better myself, I have another question: what if you are bereaved but, for whatever reason, don't have the acting skills to represent the deceased to the other mourners?

Is Miss Manners saying you shouldn't attend the funeral in that case? Is there an etiquette-sanctioned way to attend the funeral but avoid people?

The family member whose behaviour so appalled the letter-writer and Miss Manners is the deceased's daughter's aunt, which, by my math, makes her either the deceased's sister or sister-in-law.

If we were to make a hierarchy about such things, the general consensus would be that the deceased's sister attending the funeral is more important than the members of the deceased's church getting their emotional needs attended to. If we were to analyze the situation under Ring Theory, the sister would be the one who gets to do the dumping, and the letter-writer would be the one who has to do the comforting.

So would Miss Manners advise a person on an inner ring to skip a funeral if they can't attend to the emotional needs of a person on an outer ring? Or does etiquette have something else in mind for people who, in their grief, just can't hold it together enough to fulfill the requirements of etiqutte?

Labels:

advice columns,

musings,

things i don't understand

Wednesday, September 26, 2018

Demontage

As I was struggling through yet another tedious round of vision therapy, I found myself thinking that if this were a movie, it would be portrayed as a heroic training montage, jumping between Brock string beads to the beat of Eye of the Tiger.

It occurs to me that it could be creatively interesting to do the opposite - show a character going through the slow, tedious practice of practicing or building up their skills over time, until, at a crucial plot juncture, they turn out to ultimately be highly competent at the skill they're seen practicing.

This would probably be more suited to a TV series than to a movie. The character would be seen training/practicing in the background, or as the slice of life activity they're doing when they get interrupted by the episode's main plot. (Is there a word for that concept?) Perhaps their training/practice equipment is seen in a corner of their room. It could be fun to show but not tell - the character is frequently seen training or practicing in the background, but there's never an expositiony "So how's your training going?" conversation.

It might even work to have the character experience the failure or setback that leads to the training early in the season - as nothing more than a subplot, perhaps even as a background event or a passing joke or the slice of life activity that gets interrupted by the episode's main plot - then they work hard at their training in the background all season with the main plot taking centre stage, and the fruits of their hard work become a crucial plot point in the season finale.

Just as all of us who are slogging through something in real life, without the ability to save time by doing it by montage, hope that it will eventually pay off at a crucial plot point.

It occurs to me that it could be creatively interesting to do the opposite - show a character going through the slow, tedious practice of practicing or building up their skills over time, until, at a crucial plot juncture, they turn out to ultimately be highly competent at the skill they're seen practicing.

This would probably be more suited to a TV series than to a movie. The character would be seen training/practicing in the background, or as the slice of life activity they're doing when they get interrupted by the episode's main plot. (Is there a word for that concept?) Perhaps their training/practice equipment is seen in a corner of their room. It could be fun to show but not tell - the character is frequently seen training or practicing in the background, but there's never an expositiony "So how's your training going?" conversation.

It might even work to have the character experience the failure or setback that leads to the training early in the season - as nothing more than a subplot, perhaps even as a background event or a passing joke or the slice of life activity that gets interrupted by the episode's main plot - then they work hard at their training in the background all season with the main plot taking centre stage, and the fruits of their hard work become a crucial plot point in the season finale.

Just as all of us who are slogging through something in real life, without the ability to save time by doing it by montage, hope that it will eventually pay off at a crucial plot point.

Labels:

free ideas,

musings

Friday, September 21, 2018

Telling your relatives about DNA test results

A common theme in advice columns recently has been whether to disclose information from genealogy DNA tests to one's relatives.

Examples from a recent Ethicist:

and:

And one from Miss Manners:

I think people should err on the side of not telling relatives DNA test results they don't want to hear, for the simple reason that those relatives could choose to take a DNA test themselves if they wanted to. Sometimes people say their relatives have "the right to know", but a right isn't an obligation. I think people also have the right to choose not to find out, especially when it's non-actionable and knowing would cause them distress.

The ideal approach would be to mention to relatives before you take the test "I'm thinking of having a DNA test done. Are you interested in hearing the results?" And if they aren't interested in hearing the results, think about how you'd feel about keeping the results secret from them - especially if the results are emotionally fraught.

Also, I think before taking DNA tests, people should think about what's the worst thing they could find out. A lot of people seem to go in expecting something like "Cool, my third cousin once removed is a duchess!" or "Oh, THAT's why I have Mediterranean-calibre body hair despite my Northern European heritage!" But I've heard stories of people finding that they have the wrong number of siblings, or not enough great-grandparents.

Then think about how you'd feel if you found out the worst possible thing you could find out. Find out or figure out if your family members would also want to know the worst possible thing, and, if they wouldn't, think about what it would be like to have to keep the worst possible thing secret from them.

Then think about how these negatives weigh against the positives of finding out whathever it is you hope to find out from the DNA test.

Examples from a recent Ethicist:

I’m 45, living in the United States. My brother is two years older and lives in Australia. Neither of us gets on with our 86-year-old mother, who lives in London. Our father, whom we were both really close to, died in 1985 after a long illness. I was 13, my brother 15, and it affected us very badly with little help from our mother.I recently took a DNA test out of curiosity for the health information and couldn’t understand the result that I was 52 percent Ashkenazi Jewish. As far as I was aware, both my parents were from Jewish families going back as far as we knew. The following day, having not spoken to my mother for a year, I asked if she wouldn’t mind taking the test. She responded that it was a route that I might not want to go down. Of course, I asked why, and she just came out with the news that my father was infertile and that both myself and my brother were from artificial insemination. She told me not to tell my brother and said that she never wanted to talk about it again.I have been absolutely devastated by this news. Before speaking to my mother, I had mentioned to my brother that my DNA results appeared strange. He didn’t show too much interest. I genuinely do not know how my brother would react, as he is generally far less emotional than I. However, I am feeling a lot of guilt because I think it is everyone’s right to know such an important fact. As devastating as this news was to me, I am grateful to know the truth.Doesn’t everyone deserve to know the truth? Should I tell my brother outright, or should I inquire if he wants more details about his heritage or simply not bring it up? Should I give my mother the opportunity to tell him before I do? My concern for my mother’s request not to tell him is of secondary consideration.

and:

I recently did 23andMe to learn about my genetic health and ancestry. A week after getting my results, I received a marketing email asking if I wanted to connect to the 1,000-plus other customers to whom I was related. I thought, Why not, as I might meet a distant cousin back overseas. To my surprise, I learned I had a first cousin born the day before my older sister and given up for adoption by my now-married-for-50-years aunt and uncle. No one in my immediate family was aware that they had given up a child before marrying and subsequently having four more children — cousins with whom I grew up and spent summer vacations. I waited for my adopted cousin to reach out to me, which she did after a few weeks, and we had a nice phone conversation. She informed me that her biological parents and four siblings responded to a letter she wrote to them 12 years ago that they want no contact with her or her daughters whatsoever.Do I let my cousins know that I am now aware of what they have spent over a decade trying to conceal? I know of at least two other second cousins who also took a genetic test and learned of this genetic cousin through 23andMe. To me this seems like a ticking time bomb for my cousins and aunt and uncle. Between these mass-market genetic tests and social media, it is just a matter of time before folks learn of this secret my aunt and uncle have tried to conceal for 52 years. My new cousin seems perfectly lovely and looks exactly like her genetic younger sisters. I’m surprised they don’t want to meet her and her daughters but respect that is their choice.

Is it better to let my cousins with whom I have had a lifelong relationship know that I know this? Or do I wait until it all comes out via other channels and let them know then that I have known since 2018 and wanted to respect their desire for privacy with regards to this matter?

And one from Miss Manners:

Dear Miss Manners: My sibling and I were raised as white. I know we're not. I'm being genetically tested to prove it officially.This is not news my sibling will want, especially medically confirmed. He is wealthy and a somewhat public figure. We are not close. If I email or phone him, he will probably just ignore it, per usual.

It feels weird to tell someone who will not feel the relief I do — that now, things make sense — but who will just ignore it or still deny it. Is it best to just not contact him anymore? We do not see each other for holidays, etc. For me, this is like a brand-new start on life.

I think people should err on the side of not telling relatives DNA test results they don't want to hear, for the simple reason that those relatives could choose to take a DNA test themselves if they wanted to. Sometimes people say their relatives have "the right to know", but a right isn't an obligation. I think people also have the right to choose not to find out, especially when it's non-actionable and knowing would cause them distress.

The ideal approach would be to mention to relatives before you take the test "I'm thinking of having a DNA test done. Are you interested in hearing the results?" And if they aren't interested in hearing the results, think about how you'd feel about keeping the results secret from them - especially if the results are emotionally fraught.

Also, I think before taking DNA tests, people should think about what's the worst thing they could find out. A lot of people seem to go in expecting something like "Cool, my third cousin once removed is a duchess!" or "Oh, THAT's why I have Mediterranean-calibre body hair despite my Northern European heritage!" But I've heard stories of people finding that they have the wrong number of siblings, or not enough great-grandparents.

Then think about how you'd feel if you found out the worst possible thing you could find out. Find out or figure out if your family members would also want to know the worst possible thing, and, if they wouldn't, think about what it would be like to have to keep the worst possible thing secret from them.

Then think about how these negatives weigh against the positives of finding out whathever it is you hope to find out from the DNA test.

Labels:

advice columns,

musings

Thursday, September 06, 2018

The first cloth

Think about how you make woolen or cotton cloth.*

You get wool off a woolly animal or cotton out of a cotton plant. You card it, spin the result into thread/yarn, and then weave it into cloth.

Isn't it amazing that humanity came up with cloth at all!

Each of these steps requires specialized tools, and I can't really picture how you'd arrive at a rudimentary version before the tools exist. Even just the idea of turning fluff into string is mindblowing, to say nothing of inventing a tool that makes it happen! (While writing this, I've been watching youtube videos of how spinning wheels work, and I still don't understand how they work.)

The only thing that exists in nature that's remotely cloth-like is animal pelts. So someone had to come up with the idea of turning fluff into something that resembled animal pelts (as opposed to seeing them as two completely disparate things), and then they had to figure out a mechanism by which to do it! Because they didn't have tools for as-yet-nonexistent processes just sitting around, they probably came up with rudimentary versions of carding, spinning, weaving and sewing that did not require any specialized tools! And the results of these processes would have been useful and satisfactory enough that people kept using and refining the processes over generations until we got the old-fashioned processes and tools that are part of recorded history.

Based on what I can google, the details of how people figured this out, and all the intermediary processes and tools that were once used and subsequently obsoleted, are lost to history. Which is a tragedy, because it's fascinating and mindblowing - possibly the most complex invention that we take completely for granted!

*Linen and silk are also types of cloth that predate recorded history. They have comparably complex, multi-step processes, but I don't understand them as well and you can google them just as well as I can. There are likely also other types of cloth I haven't heard of in other cultures whose histories I'm not up on. And there may well be yet more that were tried and obsoleted prior to recorded history.

You get wool off a woolly animal or cotton out of a cotton plant. You card it, spin the result into thread/yarn, and then weave it into cloth.

Isn't it amazing that humanity came up with cloth at all!

Each of these steps requires specialized tools, and I can't really picture how you'd arrive at a rudimentary version before the tools exist. Even just the idea of turning fluff into string is mindblowing, to say nothing of inventing a tool that makes it happen! (While writing this, I've been watching youtube videos of how spinning wheels work, and I still don't understand how they work.)

The only thing that exists in nature that's remotely cloth-like is animal pelts. So someone had to come up with the idea of turning fluff into something that resembled animal pelts (as opposed to seeing them as two completely disparate things), and then they had to figure out a mechanism by which to do it! Because they didn't have tools for as-yet-nonexistent processes just sitting around, they probably came up with rudimentary versions of carding, spinning, weaving and sewing that did not require any specialized tools! And the results of these processes would have been useful and satisfactory enough that people kept using and refining the processes over generations until we got the old-fashioned processes and tools that are part of recorded history.

Based on what I can google, the details of how people figured this out, and all the intermediary processes and tools that were once used and subsequently obsoleted, are lost to history. Which is a tragedy, because it's fascinating and mindblowing - possibly the most complex invention that we take completely for granted!

*Linen and silk are also types of cloth that predate recorded history. They have comparably complex, multi-step processes, but I don't understand them as well and you can google them just as well as I can. There are likely also other types of cloth I haven't heard of in other cultures whose histories I'm not up on. And there may well be yet more that were tried and obsoleted prior to recorded history.

Labels:

firsties,

musings,

thoughts from the shower

Sunday, August 19, 2018

The first shapes

Circle, square, triangle, rectangle. Shapes are an extremely basic thing taught to toddlers, alongside letters and numbers and colours and animals.

But they're also rather an artificial human construct.

I mean, some shapes do exist in nature, but most of nature is irregular in shape. Prehistoric humans could have gone a lifetime without ever seeing a triangle, so they probably didn't feel the need to name it. And if they did name it, they wouldn't feel the need to teach it to children as a basic core concept.

Shapes would probably become more common as humans started making things, and standardizing the thing they're making. Then they would need to communicate what the things should look like, so they'd need names for shapes.

Would some time have elapsed between the naming of shapes and teaching them to children as a basic concept? On one hand, if they were a fairly new human invention, people might not feel they're a basic concept that small children need to know. On the other hand, in the past children have been closer to their parents' livelihoods, so they would likely learn the vocabulary of their parents' trades and/or the tasks of everyday living early on simply as a matter of course.

It's also interesting to think about the time between when people started making things but hadn't yet named shapes. If you don't have a word for a shape, you're less likely to be thinking in terms of shapes. Therefore, people probably didn't see it as necessary for things to be a particular shape in the way we do today. For example, you probably aren't going to think that the rocks around the fire need to be in a circle if you don't have a word for a circle. You probably aren't going to think your room needs to be rectangular if you don't have a word for a rectangle. Why should flatbread be round? Why should a tent be triangular? Things might have been all kinds of funny shapes simply because people didn't have the vocabulary for standard shapes!

Also, what constitutes a "standard" shape may well have varied depending on what kinds of things a particular society made. If you live in a teepee, you might have a word for triangle or cone, but not a word for rectangle or cube. If you live in an igloo, you might have a word for circle or dome, but not triangle. The internet tells me that igloos are made of blocks of ice, but perfectly cubic blocks won't make a perfectly hemispherical dome, so maybe your concept of what constitutes a "block" or a "dome" is affected by this fact.

And then, after millennia of no shapes, and millennia of shapes being the result of what people made, we somehow transitioned into theoretical shapes - perfect circles, squares, triangles and rectangles. Which affected the shapes of things people made, and eventually became so commonplace that they were no longer just for mathematicians and architects and engineers, but instead taught to preschoolers.

But they're also rather an artificial human construct.

I mean, some shapes do exist in nature, but most of nature is irregular in shape. Prehistoric humans could have gone a lifetime without ever seeing a triangle, so they probably didn't feel the need to name it. And if they did name it, they wouldn't feel the need to teach it to children as a basic core concept.

Shapes would probably become more common as humans started making things, and standardizing the thing they're making. Then they would need to communicate what the things should look like, so they'd need names for shapes.

Would some time have elapsed between the naming of shapes and teaching them to children as a basic concept? On one hand, if they were a fairly new human invention, people might not feel they're a basic concept that small children need to know. On the other hand, in the past children have been closer to their parents' livelihoods, so they would likely learn the vocabulary of their parents' trades and/or the tasks of everyday living early on simply as a matter of course.

It's also interesting to think about the time between when people started making things but hadn't yet named shapes. If you don't have a word for a shape, you're less likely to be thinking in terms of shapes. Therefore, people probably didn't see it as necessary for things to be a particular shape in the way we do today. For example, you probably aren't going to think that the rocks around the fire need to be in a circle if you don't have a word for a circle. You probably aren't going to think your room needs to be rectangular if you don't have a word for a rectangle. Why should flatbread be round? Why should a tent be triangular? Things might have been all kinds of funny shapes simply because people didn't have the vocabulary for standard shapes!

Also, what constitutes a "standard" shape may well have varied depending on what kinds of things a particular society made. If you live in a teepee, you might have a word for triangle or cone, but not a word for rectangle or cube. If you live in an igloo, you might have a word for circle or dome, but not triangle. The internet tells me that igloos are made of blocks of ice, but perfectly cubic blocks won't make a perfectly hemispherical dome, so maybe your concept of what constitutes a "block" or a "dome" is affected by this fact.

And then, after millennia of no shapes, and millennia of shapes being the result of what people made, we somehow transitioned into theoretical shapes - perfect circles, squares, triangles and rectangles. Which affected the shapes of things people made, and eventually became so commonplace that they were no longer just for mathematicians and architects and engineers, but instead taught to preschoolers.

Labels:

firsties,

musings,

thoughts from the shower

Saturday, August 04, 2018

Things They Should Study (or publicize, if they've already studied it): to what extent do social programs make life easier for employers?

I am truly terrible at washing my windows. Every time I wash them, they end up covered in streaks - basically I'm just rearranging the streaks a couple of times a year.

I've considered on and off hiring someone to wash my windows, but I have no idea how to hire someone good. I'd be happy to pay well for completely streak-free windows, but if they're just going to rearrange the streaks, that isn't worth anything to me - I can do that myself.

The problem, of course, is that all window-washers and any number of random odd-job people are incentivized to say "Of course I can give you streak-free windows!" They need money. They need to hustle. Conventional wisdom is that you should apply for jobs even if you aren't confident you can do them.

But this makes it much harder to find someone who actually is good - especially if, like me, you're unaccustomed to hiring people - so I end up hiring no one.

I have heard small business owners make similar complaints - they're often in the market for skilled, competent help before they're in a position to put resources into long-term development, but, because they don't have much experience with hiring, they have trouble finding/identifying people who actually are skilled and competent in and among all the gumption/desperation applicants, so they often end up not hiring at all.

In the shower the other day, it occurred to me that basic income might improve this situation. An effective basic income program would eliminate the desperation factor, so employer and prospective employee could have a straightforward conversation about their needs and abilities.

So I could say "What I really want is completely streakless windows. A cleaning job that results in streaks has no value to me. Are you able to guarantee streaklessness?"

And my prospective window cleaner would have the leeway to say "You know, I don't think I can do a job that could make you happy." Or to quote me a ridiculously high price since I'm so needy and demanding, which I can then accept or reject depending on what it's worth to me.

And my prospective window cleaner would be far less likely to be a person who's bad at cleaning windows, because people who are bad at cleaning windows aren't going to be going around looking for window cleaning jobs.

I did one brief, cursory google and couldn't find much on how basic income interacts with the hiring experience from an employer's point of view. So I started looking into the logistics of Ontario's basic income pilot, to see whether it could produce relevant results . . . and, that very day, the government cancelled the basic income pilot.

***

In recent discussions of introducing pharmacare, I was surprised to see the idea raised of pharmacare covering people who don't already have a drug plan through work.

That seems like an administrative nightmare. (How will the government know who does and doesn't have drug coverage through work? Will pharmacare cover my the large co-pay in my workplace plan? Do we have to worry about coverage gaps if we lose our job?)

But it also seems like it would be a lot more convenient for employers if pharmacare were universal. Employers wouldn't have to administer or pay for drug plans any more. Employers who don't provide drug plans wouldn't lose quality employees who can pick and choose to other employers with better benefits. And employers who already provide good benefits would immediately realize significant savings by not having to do so any more.

***

When they were talking about creating an Ontario pension plan, they were also talking about having it apply only to people who don't have pensions through work.

Again, it seems like it would be far more convenient for employers if the public pension plan covered everyone, for exactly the same reasons. It would save employers the trouble of administering a pension plan, employers who are unable to provide a pension plan wouldn't lose out on quality talent, and employers who already provide a pension plan would immediately realize significant savings by not having to do so any more.

***

Discourse about social programs tends to focus on what it can do for regular people, which is, of course, where the focus in planning and delivering social programs should be.

However, I've noticed a strong correlation between people who are opposed to social programs and people whose roles involve hiring. I also remember seeing things from time to time where organizations representing small businesses object to the fact that government employees receive benefits, presumably because their tax dollars are supporting providing benefits that they can't offer their own employees.

It would be useful to have the data to quantify how social programs can make life easier for employers, in addition to making life easier for ordinary people.

I've considered on and off hiring someone to wash my windows, but I have no idea how to hire someone good. I'd be happy to pay well for completely streak-free windows, but if they're just going to rearrange the streaks, that isn't worth anything to me - I can do that myself.

The problem, of course, is that all window-washers and any number of random odd-job people are incentivized to say "Of course I can give you streak-free windows!" They need money. They need to hustle. Conventional wisdom is that you should apply for jobs even if you aren't confident you can do them.

But this makes it much harder to find someone who actually is good - especially if, like me, you're unaccustomed to hiring people - so I end up hiring no one.

I have heard small business owners make similar complaints - they're often in the market for skilled, competent help before they're in a position to put resources into long-term development, but, because they don't have much experience with hiring, they have trouble finding/identifying people who actually are skilled and competent in and among all the gumption/desperation applicants, so they often end up not hiring at all.

In the shower the other day, it occurred to me that basic income might improve this situation. An effective basic income program would eliminate the desperation factor, so employer and prospective employee could have a straightforward conversation about their needs and abilities.

So I could say "What I really want is completely streakless windows. A cleaning job that results in streaks has no value to me. Are you able to guarantee streaklessness?"

And my prospective window cleaner would have the leeway to say "You know, I don't think I can do a job that could make you happy." Or to quote me a ridiculously high price since I'm so needy and demanding, which I can then accept or reject depending on what it's worth to me.

And my prospective window cleaner would be far less likely to be a person who's bad at cleaning windows, because people who are bad at cleaning windows aren't going to be going around looking for window cleaning jobs.

I did one brief, cursory google and couldn't find much on how basic income interacts with the hiring experience from an employer's point of view. So I started looking into the logistics of Ontario's basic income pilot, to see whether it could produce relevant results . . . and, that very day, the government cancelled the basic income pilot.

***

In recent discussions of introducing pharmacare, I was surprised to see the idea raised of pharmacare covering people who don't already have a drug plan through work.

That seems like an administrative nightmare. (How will the government know who does and doesn't have drug coverage through work? Will pharmacare cover my the large co-pay in my workplace plan? Do we have to worry about coverage gaps if we lose our job?)

But it also seems like it would be a lot more convenient for employers if pharmacare were universal. Employers wouldn't have to administer or pay for drug plans any more. Employers who don't provide drug plans wouldn't lose quality employees who can pick and choose to other employers with better benefits. And employers who already provide good benefits would immediately realize significant savings by not having to do so any more.

***

When they were talking about creating an Ontario pension plan, they were also talking about having it apply only to people who don't have pensions through work.

Again, it seems like it would be far more convenient for employers if the public pension plan covered everyone, for exactly the same reasons. It would save employers the trouble of administering a pension plan, employers who are unable to provide a pension plan wouldn't lose out on quality talent, and employers who already provide a pension plan would immediately realize significant savings by not having to do so any more.

***

Discourse about social programs tends to focus on what it can do for regular people, which is, of course, where the focus in planning and delivering social programs should be.

However, I've noticed a strong correlation between people who are opposed to social programs and people whose roles involve hiring. I also remember seeing things from time to time where organizations representing small businesses object to the fact that government employees receive benefits, presumably because their tax dollars are supporting providing benefits that they can't offer their own employees.

It would be useful to have the data to quantify how social programs can make life easier for employers, in addition to making life easier for ordinary people.

Labels:

in the news,

musings,

politics,

research ideas,

thoughts from the shower

Saturday, July 28, 2018

Do culture that value biological paternity produce more people who don't want children?

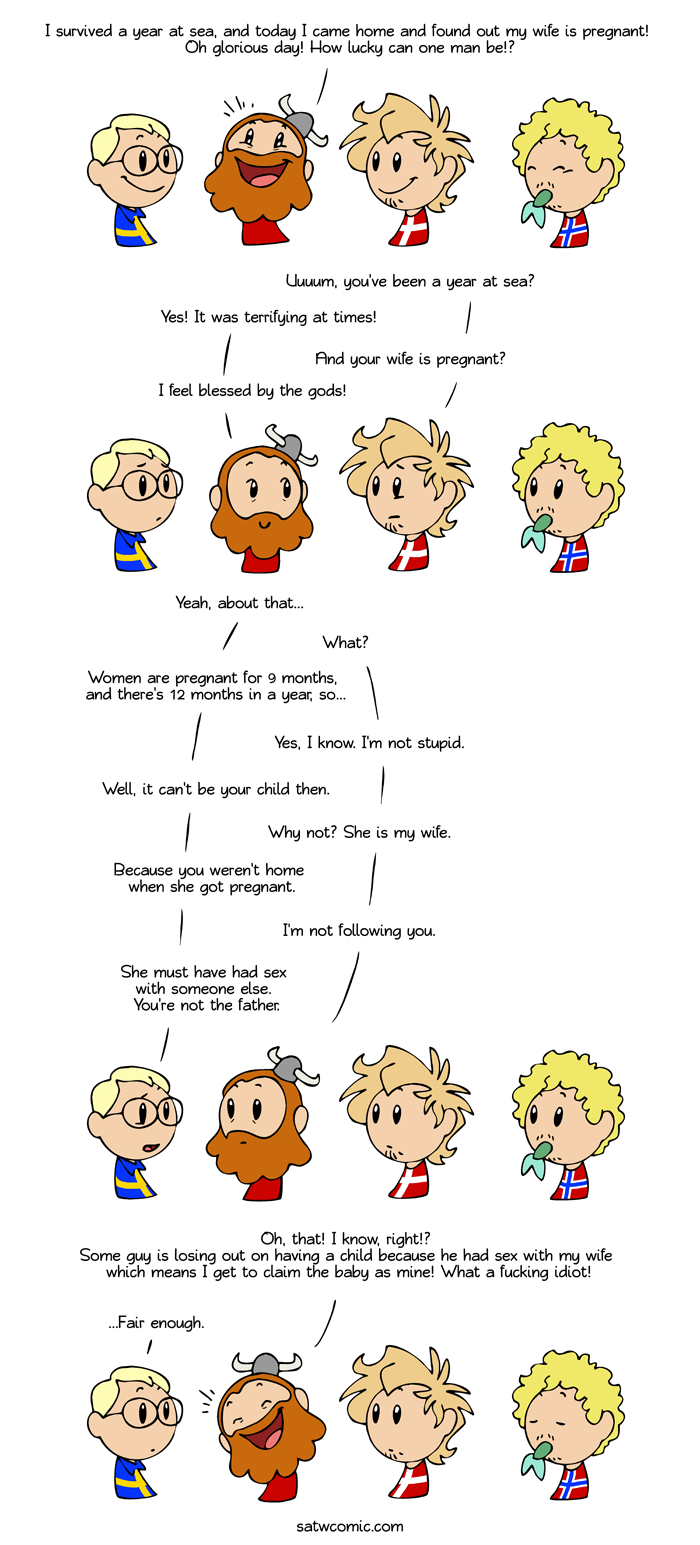

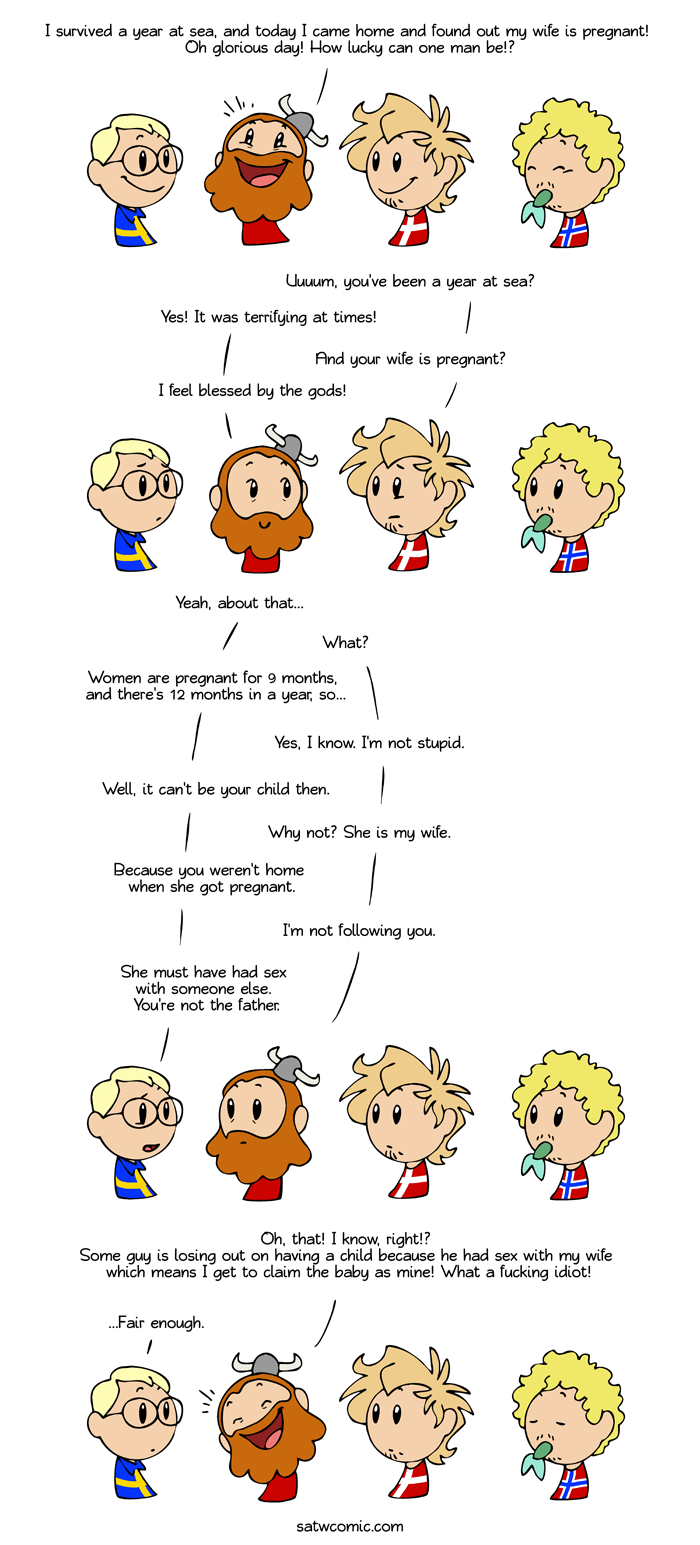

Today's post was inspired by this Scandinavia and the World comic:

The post under the comic:

(Some of the commenters suggest that this might not be historically accurate, but that's not relevant to what I'm blogging about today.)

Reading this comic, I found myself wondering if living in a culture that values biological paternity increases the likelihood that people will realize they don't want children of their own.

How I arrived at this idea:

Every adult around me growing up would have said, with absolute certainty, that having children is a blessing and a gift and a wonderful thing.

And every adult around me growing up would have said, with absolute certainty, that's it would be a horrific burden and the epitome of injustice for a man to end up raising another man's biological child.

Not so much of a blessing and a gift and a wonderful thing, that.

I think (although I can't be certain) my first exposure to the idea of children being work/a burden (as opposed to simply being baseline human reality) had something to do with this idea of raising another man's biological child being the epitome of injustice. I can't remember the details - it was probably something I absorbed from adults having adult conversation around me - but reading the comic stirred in me the forgotten knowledge that the two are inexorably linked in my mind.

I wonder: if I had never been exposed to the idea that raising another man's biological child is an injustice, and therefore to the idea that a child can be an undue burden, would I have entered the thought process that led me to realize I'm childfree? I think I'd probably still be childfree - essentially, I don't want children because I don't want actual human beings with thoughts and feelings and human rights that I need to keep forever - but I don't know if I'd ever consciously realize it. I might have been stuck on "Aww, babies are cute and funny and interesting!" and had children (or aspired to have children) on that basis.

I don't know if this could be studied - you'd need a population that thinks children are a gift regardless of biology and have access to reliable family planning and whose family planing intentions can be known (i.e. they have to be living or have a very robust and thorough diary culture, they'd have to be willing to speak honestly to researchers, etc.) And then, I'm sure, you'd need other comparable populations who don't think children are a gift regardless of biology but are comparable in every other respect, in order to control for variables that I can't even imagine. And then there's the question of which is cause and which is effect: do people see raising non-biological children as a burden because they value biological paternity? Or do they value biological paternity because they see raising children in general as a burden, so if the kid doesn't even have your genes why bother?

But it would be super interesting to study if it could be done!

The post under the comic:

Something that was deeply offensive to most of the cultures the Vikings encountered was that Vikings didn't worry too much about fidelity, even the women could shag around, and their husbands happily accepted the children as their own even if they knew they weren't the father.

The reason was quite simple. Keeping a child alive was difficult back then so any child that survived was a miracle, and people wanted big families, so if your wife had a child it was your right as the husband to keep it. The other loser could mob around with one child less to his name.

(Some of the commenters suggest that this might not be historically accurate, but that's not relevant to what I'm blogging about today.)

Reading this comic, I found myself wondering if living in a culture that values biological paternity increases the likelihood that people will realize they don't want children of their own.

How I arrived at this idea:

Every adult around me growing up would have said, with absolute certainty, that having children is a blessing and a gift and a wonderful thing.

And every adult around me growing up would have said, with absolute certainty, that's it would be a horrific burden and the epitome of injustice for a man to end up raising another man's biological child.

Not so much of a blessing and a gift and a wonderful thing, that.

I think (although I can't be certain) my first exposure to the idea of children being work/a burden (as opposed to simply being baseline human reality) had something to do with this idea of raising another man's biological child being the epitome of injustice. I can't remember the details - it was probably something I absorbed from adults having adult conversation around me - but reading the comic stirred in me the forgotten knowledge that the two are inexorably linked in my mind.

I wonder: if I had never been exposed to the idea that raising another man's biological child is an injustice, and therefore to the idea that a child can be an undue burden, would I have entered the thought process that led me to realize I'm childfree? I think I'd probably still be childfree - essentially, I don't want children because I don't want actual human beings with thoughts and feelings and human rights that I need to keep forever - but I don't know if I'd ever consciously realize it. I might have been stuck on "Aww, babies are cute and funny and interesting!" and had children (or aspired to have children) on that basis.

I don't know if this could be studied - you'd need a population that thinks children are a gift regardless of biology and have access to reliable family planning and whose family planing intentions can be known (i.e. they have to be living or have a very robust and thorough diary culture, they'd have to be willing to speak honestly to researchers, etc.) And then, I'm sure, you'd need other comparable populations who don't think children are a gift regardless of biology but are comparable in every other respect, in order to control for variables that I can't even imagine. And then there's the question of which is cause and which is effect: do people see raising non-biological children as a burden because they value biological paternity? Or do they value biological paternity because they see raising children in general as a burden, so if the kid doesn't even have your genes why bother?

But it would be super interesting to study if it could be done!

Wednesday, July 11, 2018

What if Star Trek: Discovery could desexualize the miniskirt uniform?

I recently saw an article saying that Star Trek: Discovery should use unisex miniskirt uniforms. The article quoted Nichelle Nichols:

But what if, in addition to making the miniskirts gender-neutral, Star Trek: Discovery could make them non-sexy?

Imagine if the most prominent occurrence of the miniskirt uniform was a person whom modern television costuming standards would not normally put in a miniskirt. Someone whose legs are hairier than average. Someone whose thighs rub together below the hemline of the skirt. Someone noticeably older than the rest of the cast.

For example, maybe 10% of the background cast is in miniskirts (at least 50% of whom are male), and maybe one or two characters who have "Aye, Captain" sort of lines are seen wearing miniskirts in one or two brief scenes. And then the most prominent instance of a miniskirt is on a stout, battle-hardened octogenarian admiral, with a reputation for being a brilliant military tactician as well as a bit of a hardass (like Captain Jellico), who is called in for some particularly dire crisis where particular bravery, heroics and expertise are required. And throughout, the camerawork is done exactly the same way it would be if everyone is wearing pants, neither lingering on nor ignoring any particular character's legs.

From a production perspective, this would be difficult to carry off well. First of all, every actor deserves the dignity of flattering, thoughtful costuming, and non-sexy miniskirts would not be perceived as flattering. Secondly, there's a history of putting revealing female-coded clothing on performers who aren't women who meet the narrow Hollywood definition of sexy and presenting it as comedic. ("HA HA HA! Look at that dude's hairy man-legs in that miniskirt!") It would be absolutely essential to avoid inadvertently doing this, and I don't know whether they could avoid having the less-savoury parts of the audience interpret the scene that way.

But if they could carry it off, it would disarm the unfortunate connotations of the miniskirt uniform and reclaim its original empowering intention s in a way that's consistent with woke Star Trek: Discovery values and with Federation values.

“The show was created in the age of the miniskirt, and the crew women’s uniforms were very comfortable. Contrary to what many may think today, no one really saw it as demeaning back then. In fact, the miniskirt was a symbol of sexual liberation. More to the point, though, in the twenty-third century, you are respected for your abilities regardless of what you do or do not wear.”I absolutely agree that, when Discovery inevitably runs up against the original series uniforms (which, being set about 10 years before TOS, it will if it has a full run), it should present the miniskirt uniforms as unisex/gender-neutral, like TNG briefly did before it phased them out entirely.

But what if, in addition to making the miniskirts gender-neutral, Star Trek: Discovery could make them non-sexy?

Imagine if the most prominent occurrence of the miniskirt uniform was a person whom modern television costuming standards would not normally put in a miniskirt. Someone whose legs are hairier than average. Someone whose thighs rub together below the hemline of the skirt. Someone noticeably older than the rest of the cast.

For example, maybe 10% of the background cast is in miniskirts (at least 50% of whom are male), and maybe one or two characters who have "Aye, Captain" sort of lines are seen wearing miniskirts in one or two brief scenes. And then the most prominent instance of a miniskirt is on a stout, battle-hardened octogenarian admiral, with a reputation for being a brilliant military tactician as well as a bit of a hardass (like Captain Jellico), who is called in for some particularly dire crisis where particular bravery, heroics and expertise are required. And throughout, the camerawork is done exactly the same way it would be if everyone is wearing pants, neither lingering on nor ignoring any particular character's legs.

From a production perspective, this would be difficult to carry off well. First of all, every actor deserves the dignity of flattering, thoughtful costuming, and non-sexy miniskirts would not be perceived as flattering. Secondly, there's a history of putting revealing female-coded clothing on performers who aren't women who meet the narrow Hollywood definition of sexy and presenting it as comedic. ("HA HA HA! Look at that dude's hairy man-legs in that miniskirt!") It would be absolutely essential to avoid inadvertently doing this, and I don't know whether they could avoid having the less-savoury parts of the audience interpret the scene that way.

But if they could carry it off, it would disarm the unfortunate connotations of the miniskirt uniform and reclaim its original empowering intention s in a way that's consistent with woke Star Trek: Discovery values and with Federation values.

Labels:

free ideas,

musings,

star trek

Tuesday, July 03, 2018

What if construction workers weren't even allowed on construction sites during quiet hours?

The most frustrating thing about all the construction near me is the frequency with which they wake me up by starting work early. City of Toronto noise bylaws state that construction can't start before 7 a.m. on weekdays and 9 a.m. on Saturdays, but all too often they're out there making noise before that.

The thing is, I think that most of the time when they're making noise too early, they think they're not working yet. I think they think they're just getting ready to work.

The noise that wakes me up is stuff like gates opening, trucks being backed up, the external elevator operating, and equipment being moved into position (note to construction sites: moving dumpsters around is the single loudest thing you do!).

Then, at 7 on the dot, the noise picks up - big loud whirring machines spring into action, millions of people start hitting things with millions of hammers, etc. As though they were waiting until 7 to start all this stuff, as though they thought the stuff they were doing before 7 didn't count.

But, nevertheless, the stuff they were doing before 7 still woke me up.

Idea: what if construction workers weren't even allowed on the construction sites before 7? That way they couldn't possibly make noise to wake people up, regardless of whether they think they're working or not.

It would also be easier for by-law officers to enforce (if we ever get by-law officers working outside of business hours - and I'm strongly confident that such an initiative would pay for itself in fines collected if they patrolled the Yonge and Eglinton area between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m.) because if there is any activity or worker presence whatsoever before 7 a.m., that's a violation. Gate open? Trucks present? Violation. No debating whether work is being done or not, instead it's a hard and fast "yes or no" question.

On top of that, it would make life easier for workers by disincentivizing the employer from requiring them to report to work obscenely early. The earliest I was ever woken up by construction was 5:36 a.m. - and this was in the middle of winter! Imagine how early they had to wake up on a cold winter's morning to get to the construction site in time to wake me up that early! But if the construction company got fined for workers being on the site early, the employer wouldn't make them come so early, and would in fact order them to "sleep in" another hour and a half so they aren't there before 7.

The thing is, I think that most of the time when they're making noise too early, they think they're not working yet. I think they think they're just getting ready to work.

The noise that wakes me up is stuff like gates opening, trucks being backed up, the external elevator operating, and equipment being moved into position (note to construction sites: moving dumpsters around is the single loudest thing you do!).

Then, at 7 on the dot, the noise picks up - big loud whirring machines spring into action, millions of people start hitting things with millions of hammers, etc. As though they were waiting until 7 to start all this stuff, as though they thought the stuff they were doing before 7 didn't count.

But, nevertheless, the stuff they were doing before 7 still woke me up.

Idea: what if construction workers weren't even allowed on the construction sites before 7? That way they couldn't possibly make noise to wake people up, regardless of whether they think they're working or not.

It would also be easier for by-law officers to enforce (if we ever get by-law officers working outside of business hours - and I'm strongly confident that such an initiative would pay for itself in fines collected if they patrolled the Yonge and Eglinton area between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m.) because if there is any activity or worker presence whatsoever before 7 a.m., that's a violation. Gate open? Trucks present? Violation. No debating whether work is being done or not, instead it's a hard and fast "yes or no" question.

On top of that, it would make life easier for workers by disincentivizing the employer from requiring them to report to work obscenely early. The earliest I was ever woken up by construction was 5:36 a.m. - and this was in the middle of winter! Imagine how early they had to wake up on a cold winter's morning to get to the construction site in time to wake me up that early! But if the construction company got fined for workers being on the site early, the employer wouldn't make them come so early, and would in fact order them to "sleep in" another hour and a half so they aren't there before 7.

Monday, July 02, 2018

A new colour

A common thought experiment is "imagine a new colour", i.e. a colour that no one has ever seen before.

But that must have been a thing that has happened in human history.

On an individual level, there's the fact that there's a first time for every life experience, including the first time you see each colour. If there isn't any orange within your immediate field of vision when you're born, you will one day see orange for the first time. You probably won't realize that you're seeing a new colour, because you're experiencing all kinds of new weirdness, like eating and peeing and breathing and air and light, but the fact is you did, at some point, see orange for the first time.

But it might also have happened on a societal level. Within the full scope of human history, people have lived (and still do live) in some pretty desolate environments. In the past, where people didn't travel very long distances and didn't have access to dyes, maybe there have been societies living in the Arctic or the Sahara who went years without seeing a particular colour, because it simply wasn't present in their environment.

Then, one day, someone goes on a journey, sees a new flower, and OMG, what is that colour???

But that must have been a thing that has happened in human history.

On an individual level, there's the fact that there's a first time for every life experience, including the first time you see each colour. If there isn't any orange within your immediate field of vision when you're born, you will one day see orange for the first time. You probably won't realize that you're seeing a new colour, because you're experiencing all kinds of new weirdness, like eating and peeing and breathing and air and light, but the fact is you did, at some point, see orange for the first time.

But it might also have happened on a societal level. Within the full scope of human history, people have lived (and still do live) in some pretty desolate environments. In the past, where people didn't travel very long distances and didn't have access to dyes, maybe there have been societies living in the Arctic or the Sahara who went years without seeing a particular colour, because it simply wasn't present in their environment.

Then, one day, someone goes on a journey, sees a new flower, and OMG, what is that colour???

Sunday, July 01, 2018

The voice in your head vs. the voice outside your head

The first time I ever heard a recording of my voice, I was completely weirded out. My voice sounds nothing like it does in my head! (And everything about it is gross, but that's a whole nother story.)

Many, if not most, if not all people feel that way about hearing recordings of their voice. It just sounds so different! (I wonder if anyone thinks their recorded voice sounds better than the voice in their head?)

This is why I'm surprised that vocal impersonations/impressions are a thing. We sound so different outside our heads that I'm surprised anyone can even do a vocal impersonation that is recognizable to anyone outside their head.

Or do they record themselves, see what their attempt sounds like, and adjust accordingly? Then you'd have to remember what an accurate impression sounds like inside your head.

I wonder if they eventually develop the ability to determine "If I sound this way inside my head, I must sound exactly like Famous Person to others."

Or do people who can do accurate vocal impressions sound the same both inside and outside their head?

I wonder if vocal impersonations existed before recording technology? I wonder if they were less accurate/recognizable than they are now?

Many, if not most, if not all people feel that way about hearing recordings of their voice. It just sounds so different! (I wonder if anyone thinks their recorded voice sounds better than the voice in their head?)

This is why I'm surprised that vocal impersonations/impressions are a thing. We sound so different outside our heads that I'm surprised anyone can even do a vocal impersonation that is recognizable to anyone outside their head.

Or do they record themselves, see what their attempt sounds like, and adjust accordingly? Then you'd have to remember what an accurate impression sounds like inside your head.

I wonder if they eventually develop the ability to determine "If I sound this way inside my head, I must sound exactly like Famous Person to others."

Or do people who can do accurate vocal impressions sound the same both inside and outside their head?

I wonder if vocal impersonations existed before recording technology? I wonder if they were less accurate/recognizable than they are now?

Labels:

musings

Sunday, June 24, 2018

The logistics of being rich

When you go through customs, they ask you if you packed your baggage yourself.

But very rich people probably don't - they probably have their personal assistant or whatever pack their bags.

So how does that conversation go? "No, of course I didn't back my own bags - I had my assistant do it." Then what happens? Do they need to question the assistant? What if the assistant isn't there?

Rich people also probably don't wait on hold - they have their assistant call the cable company. But often when I make these kinds of phone calls, they verify my identity. So how does that work? Does the assistant pretend to be their employer? Does the employer have the assistant added to their account? Do they have to change a whole bunch of accounts every time they get a new assistant?

When I make an appointment, I have all kinds of preferences. Ideally after 4:30, although I might be able to do earlier if necessary. Afternoons are better than mornings. Thursdays are worse than other days, although not completely out of the question. Certain medical appointments need to take place at certain points in my menstrual cycle. Certain beauty appointments need to be timed vis-à-vis other beauty appointments and a certain amount of time before the event in question.

Rich people don't make their own appointments, they have their assistant do it. So does the rich person have this big complex conversation about their preferences with the assistant, and then the assistant has to write all this down and convey it in making the appointment? Or does the assistant just stick the appointment in wherever the rich person has an opening on their calendar, and their preferences don't get taken into account?

But very rich people probably don't - they probably have their personal assistant or whatever pack their bags.

So how does that conversation go? "No, of course I didn't back my own bags - I had my assistant do it." Then what happens? Do they need to question the assistant? What if the assistant isn't there?

Rich people also probably don't wait on hold - they have their assistant call the cable company. But often when I make these kinds of phone calls, they verify my identity. So how does that work? Does the assistant pretend to be their employer? Does the employer have the assistant added to their account? Do they have to change a whole bunch of accounts every time they get a new assistant?

When I make an appointment, I have all kinds of preferences. Ideally after 4:30, although I might be able to do earlier if necessary. Afternoons are better than mornings. Thursdays are worse than other days, although not completely out of the question. Certain medical appointments need to take place at certain points in my menstrual cycle. Certain beauty appointments need to be timed vis-à-vis other beauty appointments and a certain amount of time before the event in question.

Rich people don't make their own appointments, they have their assistant do it. So does the rich person have this big complex conversation about their preferences with the assistant, and then the assistant has to write all this down and convey it in making the appointment? Or does the assistant just stick the appointment in wherever the rich person has an opening on their calendar, and their preferences don't get taken into account?

Labels:

musings

Friday, March 09, 2018

What if societal minimization of menstrual pain causes women to underassess their own pain?

Recently tweeted into my timeline: menstrual cramps can be as painful as heart attacks.